Connecticut

Overview

From the rolling hills of Litchfield County in the Northwest corner of the state to small, spring-fed creeks flowing into tidal marshes of Long Island Sound and just about everywhere in between, native brook trout can be found quietly finning in the waters of Connecticut. These fish are important indicators of ecological health, and Trout Unlimited is focused on securing a stronger future for them in our most intact and healthy streams. We are assessing and restoring trout habitat, removing dams and culverts to reconnect rivers and provide fish passage, and connecting communities to our mission of caring for and recovering Connecticut’s coldwater rivers and streams and its native and wild trout.

Threats & Opportunities

Connecticut’s cold, clean rivers face threats on multiple fronts, especially with climate change driving rapid warming, stronger severe weather events, and prolonged drought. We are increasing the pace of dam and culvert removal to re-open rivers for migration, restoring in-stream habitat, re-vegetating river banks with native plants that clean and cool the waters, advocating for better stormwater management to address flash flooding and polluted runoff, and investing in modern-day water and fisheries management across the state.

How We Work

Reconnection

We’re advocating for removing or improving fish passage at barriers large and small. Removing dams or other barriers, such as perched culverts, will improve habitat access in other systems, including salter brook trout streams.

Restoration

We use a variety of tools, including the Eastern Brook Trout Conservation Portfolio, to prioritize streams where habitat restoration is most needed and where it will have the most impact and best chance for long-term success. Restoration efforts include stabilizing stream banks and improving riparian health by planting native trees. Through a Regional Conservation Partnership Program, we are strategically adding wood in-stream habitat.

Protection

We are engaging landowners to protect Connecticut’s coldwater trout streams by advocating for commonsense development, working with land trusts to protect key places, and setting up conservation easements. By working with state freshwater fisheries officials, we are in a better position to advocate for needed regulatory protections.

How You Can Help

Support our work restoring and protecting local rivers and streams.

TAKE ACTIONStay up to date about how you can help us care for and recover Connecticut’s Priority Waters.

Connecticut Conservation Team Leaders

Tracy Brown

Northeast Restoration Manager

tracy.brown@tu.org

Northeast Restoration Manager

tracy.brown@tu.org

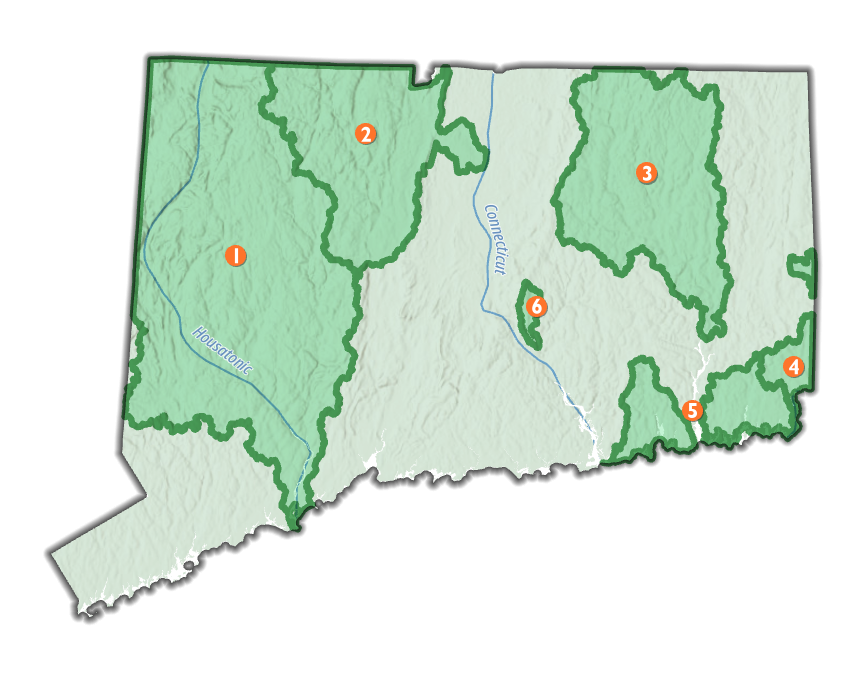

Priority Waters

-

Housatonic River

“There’s no tonic like the Housatonic” Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. Said. Though damaged and degraded by centuries of misuse and abuse, much of the Housatonic would still be familiar to him and his contemporaries, who plied the river’s waters for wild and native trout at the turn of the 20th century. The Housatonic watershed connects thousands of tributaries large and small, which tumble from wooded hills into the river valleys bringing cold, clean water and critical nutrients to the river below. The Housatonic persists as a cherished native and wild trout watershed and resonates with the history of those who came before and the promise of a better future for the fish (and anglers) who call it home today.

-

Farmington River

The crown jewel of Connecticut’s tailwater fisheries, the Farmington River draws more than 2.1 million angler visits each year, making it an economic engine of tourism for the communities surrounding the river. Home to some of the highest populations of wild and holdover brown trout, the Farmington River watershed also features many of the most intact and healthy native brook trout waters. Threading through heavily wooded and protected state forests, hundreds of small, cold tributaries bounce their way through moss-covered boulders and into the larger foothill streams, all connected to the larger river, which in its upper reaches is one of the state’s four federally designated Wild & Scenic Rivers.

-

Shetucket River

Formed by the junction of the Willimantic and Natchaug rivers, the Shetucket flows 20 miles south before joining up with the Thames River in Eastern Connecticut. The river passes a mix of farmlands and forest in its upper watershed before passing through the hearts of many towns and cities along its way. Fueled by many cold springs and seeps in its many tributary streams, the Shetucket is a popular and scenic river where anglers can cast a line for stocked and wild fish under the shadow of an historic covered bridge, or wander into the woods to chase delicate and beautiful native brook trout.

-

Pawcatuck River

A shared river between Connecticut and Rhode Island, the Pawcatuck River is part of our Wood-Pawcatuck Priority Water system. Home to some of the strongest runs of sea-run fish in the state thanks to countless dam and fish passage barrier removals, the Pawcatuck is a low-gradient water that slowly winds its way through wetlands, meadows and forests on its way out to the sea. Numerous cold springs bubble up from the rich aquifer, giving this river a promising future as a native trout refuge in the decades to come.

-

South Shore – Mystic River

Sea run brook trout, commonly called “salters,” are some of the rarest fish in the state. They require the coldest, cleanest freshwater to thrive, as well as free and open passage out to the salt waters of nearby estuaries. The range for salters—which were known to grow up to 10 pounds or more in the 1800s—has shrunk considerably. They once thrived from Long Island through Maine; today, they populate just a handful of isolated regions, especially in the southern end of their range. Dozens of these cherished salter streams remain viable in Connecticut, and many more are targets for recovery.

-

Pine Brook

Flowing for roughly seven miles from its headwaters to its confluence with the Salmon River, Pine Brook is a charming, spring-fed wild trout stream that is both well protected and offers excellent public access. Stewardship by the Middlesex Land Trust and the Silvio O. Conte National Wildlife Refuge has ensured that a large percentage of the stream, which is managed as a wild trout fishery, is open to the public via land conservation easements. Trout Unlimited is assessing the upper reaches of the watershed for barriers that restrict the movement of trout and other aquatic species.